DURING THE SUMMER of 2020, in full pandemic lockdown, I began to contemplate the future of the Scrophulariaceae bed. It is 20 feet (6 m) wide, ringed by a nine-inch-high (23 cm) granite curb, and sits at the northern terminus of the north-south spine of New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill in Boylston, Massachusetts. It needed to make a statement.

The year 2020 was the second in a multi-year transformation of the former Systematic Garden, a taxonomic garden based on the Cronquist system, built in 2001, in the Nadeau Garden of Inspiration. The layout was inspired by classic French garden design and features 22 beds arranged in a loosely symmetrical rectangle. Each bed reflected a different theme, based on cultural needs, design, or function. There are beds dedicated to sun perennials, cut flowers, foliage, fragrance, and pollinators, to name a few. But there was no rock garden. The shape of the Scrophulariaceae bed lent itself to becoming a rock garden, I thought, because it is raised and circular, so I could build up a little mountain and showcase diminutive rock garden gems. As it happened, I knew nothing about rock gardens. In gardening, as in life, I am a generalist. In my research, I quickly came across the North American Rock Garden Society and the Norman Singer Endowment Fund grant program. We pulled together an application for a grant to research rock gardens in Colorado and around the Northeast.

First stop, Denver. In Colorado, I had to let go of my notions of what a garden is and learn to see in a new way. Instead of the dominant palette of greens and blues I was accustomed to, the colors were sandy browns and rusty reds. The vegetation was gray-green and sparse. Of course, I expected this, but it was still an adjustment. What I hadn’t really understood was that the rocks themselves were a primary design element and the plants were adornments. That is wildly different from the gardens I was used to designing and seeing. I was used to the plant material defining the shape, texture, and color of the garden bed, and filling it completely.

The first garden I saw was that of Panayoti Kelaidis, senior curator and director of outreach at Denver Botanic Gardens. He had graciously invited me to his home my first night in Denver. After dinner outside on the lawn, we took a stroll around the garden. It was a classic plant lover’s garden, full of individuals, secret gems, and sentimental favorites. Because it was my first night there and I was a bit overwhelmed, I didn’t take notes or pictures. But it was the beginning of me adjusting my vision to a different kind of garden.

The next day, I traveled to Vail, to the Betty Ford Alpine Garden, where I met with Curator Nick Courtens, who graciously showed me around this beautiful garden. The tininess of many alpine plants demands that you move in close, like with a Fabergé egg. As Nick explained, rock gardens are intended to look as if they rose naturally from the earth below. Even crevice gardens, with their linear arrangement of slabs, are usually naturalistic in design. I also had the opportunity to see the work of Kenton Seth, a world-renowned crevice garden designer who not only designed crevice gardens at the Betty Ford Alpine Garden but also at Glenn Guetenberg and Patrice Van Vleet’s garden in Littleton, and Carol and Randy Shinn’s garden in Fort Collins.

In Fort Collins, I visited the extraordinary garden designed by the Shinns, of which Kenton Seth’s crevice bed was just a small part. Carol is a genius at combining individual plants into a cohesive whole, no mean feat. I was learning that rock gardens in general rely on that sort of design. I haven’t seen one that clumps like plants together or is even densely planted.

At Denver Botanic Gardens, I toured the expansive rock garden with Mike Kintgen. We talked about the naturalistic style of rock gardens. In my case, it would be impossible to create a garden that truly looks like it just grew there, because it’s in a raised bed in a formal garden. Mike’s opinion was simply that whatever direction I went, go in 100 percent.

Things were a bit different when I toured some rock gardens in the Northeast. Firstly, I focused more on the plant material, since they were more suited to my climate than what I saw in Colorado. Also, the gardens were not crevice gardens, except for the extensive and beautiful one at the Montreal Botanic Garden designed by Czech rock garden guru Zdeněk Zvolánek.

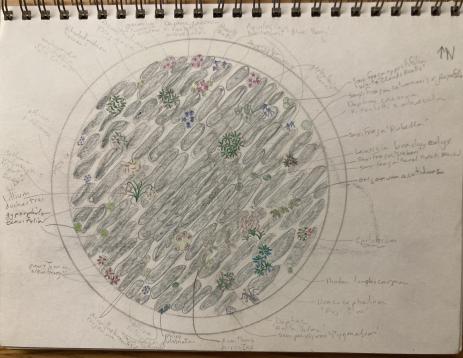

Back at home, I started work on the design. I wanted a craggy high point in the center of the bed with the line of the stones at an angle from the garden’s central axis so that those approaching through the Kinship Arbor would not be seeing the garden head-on. This would also make a shady area to the northwest for plants that won’t tolerate being blasted by sun all day.

I went searching for the rocks I would need. Initially, we investigated harvesting them on-site from the many fallen down stone walls or the plentiful shist found on the hillsides. However, I thought it would be too difficult to collect stone from the woods, so we did purchase stone from Sansoucy Stone in Worcester, which is harvested from stone walls in New England. The four large stone slabs that form the central mountain are Goshen stone, a metamorphic rock from central Massachusetts. After running out of the fieldstone from Sansoucy, I found piles of it on the property. They had been collected by our tractor operator during irrigation projects. In the end, most of the stone for the garden was from Tower Hill.

First, we laid down a 3-inch (7.6 cm) bed of ¾-inch (1.9 cm) chipped stone. The large central stones were wedged into gulleys dug in the base layer to keep them upright. Once those were in place, I arranged the remainder by hand. As I worked, I realized the ground level needed to be varied so I created hills and valleys.

From the sides, the rock garden looks like waves or mountains. The ground level swells and sinks. I poured in the fill material as I worked, and then built up to fill most of the crevices almost to the top. After allowing it to settle for a couple of weeks (which proved to be not long enough), I planted. I ordered plants from Wrightman’s Alpines and Arrowhead Alpines. I also had plants I had grown from NARGS Seed Exchange seeds, which didn’t survive the transition to the garden as well as the ordered plants. Elisabeth Zander picked out five wonderful daphnes from O’Brien’s Nursery in Connecticut for me. As the plants start to fill in the spaces between the vertical stone slabs, I will need to reassess and replant certain areas, as plants may not survive or may not be positioned in the ideal location within the crevice garden. This project has given me great joy and I hope that it will inspire visitors to our garden to experiment with rock and crevice garden designs in their own outdoor spaces.